"Ms. Mitrovic stages the attacks flamboyantly, with faux Molotov cocktails, fog machines and projections: a stark contrast to the traditional music, dancing and flowers that often accompany the immigrants’ reminiscences."

"Ms. Mitrovic stages the attacks flamboyantly, with faux Molotov cocktails, fog machines and projections: a stark contrast to the traditional music, dancing and flowers that often accompany the immigrants’ reminiscences."Danke Deutschland (2019)

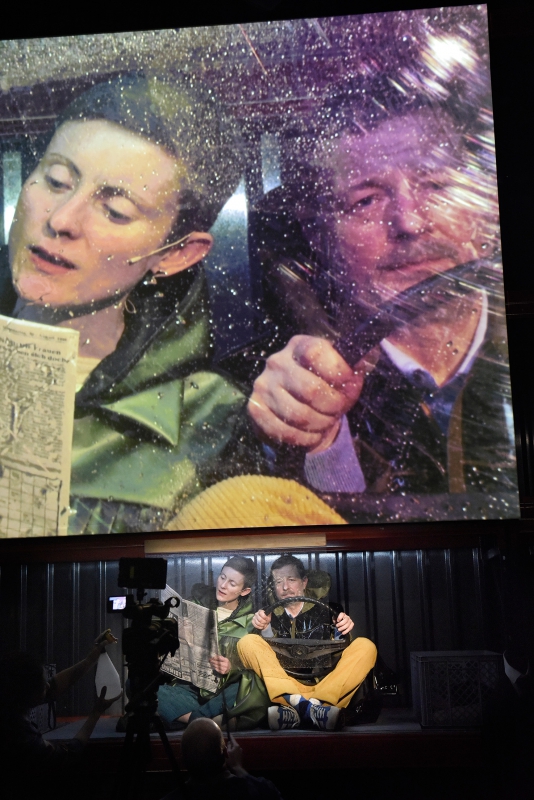

Performance with actors from the Schaubuhne ensemble and the members of the Vietnamese communityWhat defines a German citizen? How does the relationship between citizens and immigrants in German society change under shifting political conditions? There was immigration from Vietnam – under very different circumstances – in both West and East Germany. In the Federal Republic of Germany of the late 1970s, the conservative and social democratic parties strongly advocated for the acceptance of civil-war refugees from South Vietnam who had been persecuted by the victorious communists and had fled across the South Vietnamese sea as so-called »boat people«. The latter received integration sponsors, language courses, the right to free movement and had it pretty easy on the job market. The Vietnamese community sought to express its gratitude to Germany, ideally by not standing out or becoming a burden; by remaining »invisible«. Criticism, for example, of the everyday racism they experienced, was not welcome. In the GDR, contract workers from the North Vietnamese socialist brotherhood arrived from 1980 onward. They were full of hope and considered themselves to be privileged, but lived in isolation in hostels and spoke hardly any German. Further contact with the East German population was not encouraged. After the Fall of the Wall, their situation remained unresolved for years, racism flared up again – also against the Vietnamese living in West Germany. Many eventually became self-employed as small business entrepreneurs and later came to be portrayed as »exemplary migrants« who were played off against other migrant communities. Sanja Mitrović was born in Zrenjanin (former Yugoslavia) and is currently based in Brussels. After showing two productions at FIND 2016, in her first production at the Schaubühne she now looks at two reunited countries, Germany and Vietnam, in which capitalism and communism were once irreconcilable opposites. Working with actors from the Schaubühne ensemble who grew up in East or West Germany or migrated to Germany, alongside a former contract worker, »boat people« and the second generation German-Vietnamese, she explores the fault-lines, unhealed wounds and unresolved conflicts of a reunited country. She also looks at changing German ideas about good citizenship, desirable refugees, migrant workers and demonised illegals. She meets activists and humanists, racist criminal gangs, the petit bourgeois and idealistic politicians, as well as people who do not fit into any ideological pigeonholes or model, and observes how different political systems unfailingly generate new images of »us« and »them« to serve their own agendas. Danke Deutschland - Cảm ơn nước Đức at Schaubühne >>> Learn more about the production in Pearson's Preview: Be Grateful! »Danke Deutschland – Cảm ơn nước Đức« at the Schaubühne Photo by: Thomas Aurin

Cast And Credits

By Sanja Mitrović and ensemble. Direction: Sanja Mitrović. Set Design: Élodie Dauguet. Costume Design: Ivana Kličković. Video: Krzysztof Honowski. Music: Vladimir Pejković. Dramaturgy: Nils Haarmann. Research: Angelika Schmidt, Marcus Peter Tesch. Lighting Design: Giacomo Gorini. With: Veronika Bachfischer, Mai-Phuong Kollath, Denis Kuhnert, Khanh Nguyen, Felix Römer, Kay Bartholomäus Schulze, Mano Thiravong, Lukas Turtur. Duration: ca. 110 minutes.

Production: Schaubühne, Berlin (DE). Co-production with Théâtre Nanterre-Amandiers (FR). Supported by Lotto Stiftung Berlin

Press

The play »Danke Deutschland« reveals the not yet healed wounds and unresolved conflicts of the reunified Germany,

Marina Mai, Der Freitag (in English), 14.04.2019

the changing conceptions of good citizen, of desired and undesired refugees.Ms. Mitrovic stages the attacks flamboyantly, with faux Molotov cocktails, fog machines and projections: a stark contrast to the traditional music, dancing and flowers that often accompany the immigrants’ reminiscences.

[...]

In a festival packed with shows that promised to deal with explosive topics, “Danke Deutschland” was one of those that most succeeded in turning hot-button issues into convincing theater.

A.J. Goldmann, New York Times (in English), 11.04.2019Members of the ensemble share the stage with amateur actors, German-Vietnamese first and second generation immigrants. When they speak of their personal biographies the evening is most moving.

Katrin Pauly, Berliner Morgenpost (in English), 06.04.2021

When are you a citizen? When not a ‘second class citizen’ anymore? These are the good questions that are posed right at the beginning.

Doris Meierhenrich, Berliner Zeitung (in English), 08.04.2019Khanh Nguyen speaks of her father and her uncle who open a Chinese restaurant after the Wende, assuming that Germans would not like Vietnamese food. And she speaks of being doubly out of place: Dresden was a hub of North Vietnamese people whilst her family originates from the South. There is a plethora of such enlightening moments in ‘Danke Deutschland’.

Patrick Wildermann, Tagesspiegel (in English), 06.04.2019